In the past few years, the financial sector has become the first target. The financial institutions were accused of irresponsible risks, such as overleverage[1] and short-term planning.

In 2008, the crisis caused various financial institutions to gasp for breath in financial terms. They had to make up for the declining value of their assets (loans, shares, corporate bonds, debt claims on the interbanking market)[2] from the equity. Subsequently they were forced to increase this equity. In the frozen markets during the financial crisis this was only possible with financial support from the government.

Capital requirements: Basel III

Due to the crisis, the regulatory framework also became a target. The Basel II legislation that had to guarantee the soundness of the financial system appeared to have worked insufficiently during the crisis: various institutions that fulfilled all the rules perfectly also lost their balance when the crisis gained speed.

The Bank for International Settlements in Basel (BIS), where the governors of the central banks discuss the stability of the financial system at fixed times, quickly came with proposals to tighten the regulatory framework in order to increase the stability of the balance sheets of the financial institutions. The Basel III legislation, which will be implemented in various phases between 2013 and 2018, must reduce the leverage on the equity of financial institutions and reinforce their funding. This should reinforce their balance sheets both quantitatively and qualitatively.

In European law, the Basel III legislation is converted into European law via the so-called CRD IV package. This will apply to all lending institutions and investment firms throughout the European Union.

Although the financial sector advocates the Basel III legislation, it will be a challenge to continue to reconcile the capital rules with the growing (social) demand for long-term loans, for example to fund large projects such as the construction of hospitals. Definitely when the economy will recover again and the demand for loans will increase significantly, it will not become easier for financial institutions to continue to fulfil their role as funder of the economy within the Basel III framework. After all, if the financial institutions must phase out too much, this will also directly affect their added value and the extent to which they can satisfy the demand for loans.

Consumer protection: MiFID

Basel III, for that matter, is not the only legislation that intervenes in the social role of the financial institutions. Four years after the MiFID Investment Directive was issued, the European Commission tightened these rules in the MiFID II in October 2010. The suitability test that indicates whether or not an investment product corresponds with a customer’s investment profile must, for example, be executed each year from now on, even if the customer’s investment profile has not changed in the meantime.

Supervision

Banking supervision has recently been going through a number of profound changes. According to the Twin Peaks regulation, in which the Belgian supervisory structure has been laid down, the supervisory authority (NBB) for example has the power to block strategically important decisions taken by systemic banks, if one fears that they may jeopardize financial stability.

Furthermore, on a European level yet more new initiatives are still in the pipeline. One of them provides for the creation of a European banking union. This union would be under the supervision of the European Central Bank. In this way, European banking supervision will reach a higher level of uniformity.

The banking union would have one deposit guarantee system and dismantle financial institutions in trouble in a similar manner, for example with the help of a previously drawn up living will for banks.

The proposals in respect of crisis management aim to give the authorities the power to intervene at an early stage when a bank or group of banks gets into trouble. They also must ensure that, if the bank can no longer be saved, the restructuring and liquidation costs can be shifted to the bank’s owners and creditors (shareholders, bondholders, etc.) instead of to taxpayers.

The European DGS system must ensure that the savings of the Belgian citizens remain guaranteed if a bank gets into trouble. Before the crisis, savings were guaranteed up to €20,000. As a result of the events in 2007-2008, the amount has been raised to €100,000. To guarantee this, the financial institutions must of course pay higher DGS contributions.

Within the creation of a European bank union, a system is currently being developed that must put all national DGS regulations on an equal footing. We must be careful therefore with national regulations that may go against international legislation. The financial world is by definition a very international world, which is preferably regulated internationally in a coherent manner. That argument applies in the Belgian financial landscape even more than elsewhere. The Belgian landscape, after all, is very diversified and 82% of the institutions have their headquarters abroad. Regulations that reason merely nationally might therefore sometimes have an opposite effect.

The concept of a bank union also offers another perspective on the security of financial institutions. The optimal size of a financial institution is currently mainly tested against the national budget and the gross domestic product (GDP) of the country to which the institution belongs. However, the European bank union will unlink the financial institutions from the national budgets and GDPs. The question may be posed therefore if we should not anyway test the best possible size of a bank against other criteria.

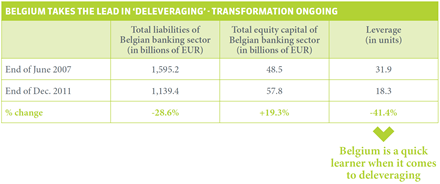

Phasing down of balance sheets in Belgian financial sector

The Belgian financial institutions have reinforced their balance sheets considerably, especially due to the phasing out of their foreign activities. At the end of March 2012, they had phased out their leverage by 41.4% compared to end June 2007. At the same time they raised their equity by 19.3% and reduced their liabilities by more than a quarter. The Belgian financial sector seems ready, therefore, to comply with the new Basel III legislation.

[1] Leverage reflects the proportion between the equity of a financial institution and its balance sheet total. An institution that is overleveraged has therefore too little capital in proportion to its total balance sheet.

[2] Loans, shares, corporate bonds, debt claims on the interbank market.